Game of Taxes

Following the death of Cromwell, and King Charles II returning from exile in Europe, an excise tax was introduced – on Christmas Day no less! The year was 1661 and the court needed to raise revenue for the battle weary Crown. Anyone distilling was obliged (although not required) to register and pay taxes. Naturally most avoided this, specifically those in the barren northwest regions of Ireland. Those responsible for enforcing the law were typically the landlords, but since much of their rental income was coming from these small-scale distilling operations, they chose to turn a blind eye to their impoverished tenants’ activities. The act of 1661 split a once homogenous native spirit, into that of illicit poitín produced rurally, and what was henceforth referred to as ‘parliament’ whiskey, produced in the tightly controlled and monitored urban centres.A Higher Quality Spirit

Upon the introduction of the act, the taxes directly impacted the quality of the parliament whiskey. The added cost pushed distillers to take drastic measures and focus more on quantity rather than quality. Coupled with rising demand, this would be a recipe for disaster. Rushed distillation runs produced excess frothing in the stills which was ‘remedied’ by using soap. Reflux and sulphur removal became less a standard in producing quality spirit, but more a luxury if time allowed. Wider ‘cuts’ made during distillation meant the resulting whiskey was near undrinkable or at worst toxic. (During distillation the ‘cut’ involves separating out the safe, potable, flavoursome ethanol, with the higher alcohols typically used for industrial purposes). In contrast, the sparsely populated regions of Donegal and the Connacht region, proved too time-consuming for the Crowns excise collectors to monitor. Illicit distilling flourished in the wake of the poorly produced parliament whiskey. With reports of over 2,000 homestills in operation at any one time, 800 of which situated up the mountains of the infamous Inishowen Peninsula, it’s clear poitín making was a deeply ingrained part of rural Ireland. Avoiding the Crown’s taxes by being well out of the radius of The Pale proved fortuitous for the small-scale distillers, allowing them to produce a superior product.Inishowen Peninsula with the mountains of Croagh Carragh, Mamore and Raghtin More

Whiskey Recovers, Poitín Suffers

Reforms of alcohol taxation laws in Ireland in the 18th century garnered the attention of industrials both at home and abroad. This sparked an increase in legal, large-scale production, particularly in the cities of Dublin, Cork and Belfast. while simultaneously driving rural distilling further underground. The quality of parliament whiskey was soon bolstered via economies of scale, and with export market access, became not only the most widely consumed whiskey in the world, but was revered amongst the upper echelons. This was of course not only due to the careful hand of the whiskey makers, but because of the unique pot still style produced at the time.Skyline of Dublin 1800’s

The Next Generation:

So while Irish whiskey has enjoyed the spotlight ever since, the humble native potion of the rural lands maintains its reputation as being Ireland’s original spirit. Very little has changed in its production process, with most producers today uprooting their long lost recipes . Many distillers today are descendants of illicit poitín makers, and have lifted their family recipes out of the shadows to showcase proudly their local distilling heritage.

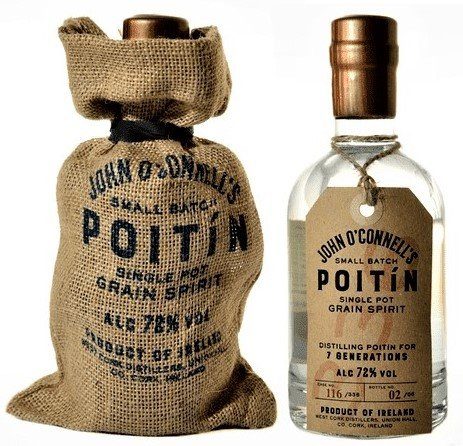

John O’ Connell of West Cork Distillers is 7th generation and incorporates sugar beets, a traditional catalyst used for fermentation, into the mash bill.

Pádraic Ó Griallais of Galway, 6th generation, named his distillery after his great-great-great grandfather, Micil Mac Chearra, who hailed from the Connemara region. His flagship poitín, Micil, uses local botanical bogbean in-line with the family recipe.

Killowen Poitín follows a local recipe based around the Mourne Mountain area, and distills with direct flame heat, the most traditional process of distilling.

The Future of Poitín

Some critics will say it’s a basic form of whiskey because it lacks any ageing properties, although legally one can age or ‘rest’ poitín for a maximum of 10 weeks, a process already being trialed by the new generation of producers, with interesting results. It’s sheer strength can be daunting to your average consumer, however one doesn’t have to look too far to see many examples available at bottle strengths akin to any whiskey. Additionally, poitín is proving itself an effective substitute in the world of mixed drinks due in part to its potency but also it’s diverse flavour profile in comparison to other unaged spirits. Considering it’s resilient tale of past times, and with upwards of 20 commercial brands of poitín available today, poitín isn’t going away anytime soon.Bar 1661 in Dublin serving the finest selection of poitin cocktails.